Airports have a key role to play in championing a city’s or country’s craft, culture, tastes and traditions. For visitors they offer the first and last impression of the locality, for that city’s citizens they provide a source of civic pride. An arts & culture programme connects passengers to a place in the same way an airport connects them to the world. Many airport companies embrace that role with pride and passion.

Introduction: Düsseldorf Airport has a vision to be a ‘destination of excellence’. Its innovative Art Walk exhibition is an example of that mission, as the airport company supports local artists while simultaneously balancing commercial interests. The airport also strives hard to inject local flavour, literally and figuratively, into its food & beverage offer and, increasingly, its retail proposition.

The Moodie Davitt Report Founder & Chairman Martin Moodie speaks to Head of Commercial Operations Pia Klauck and Media Manager Tankred Stachelhaus to discuss how Düsseldorf Airport is determined not only to serve its passengers but to surprise and even challenge them.

This article first appeared in The Moodie Davitt eZine. Click here for that version.

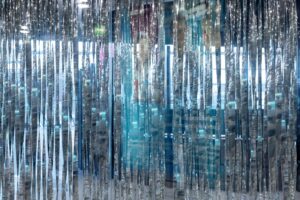

Düsseldorf Airport is far more than a transportation hub. In fact, thanks to a far-sighted management policy, it has been transformed into a vibrant cultural platform, redefining the traditional airport experience through initiatives such as the innovative Art Walk exhibition. Vacant spaces have been turned into compelling art installations and galleries that celebrate the North-Rhine Westphalia region’s rich heritage, surprising and engaging travellers as they move through the terminal.

The recently introduced Art Walk is a daring realisation of a vision to balance commercial space with an authentic cultural experience.

Düsseldorf Airport Head of Commercial Operations Pia Klauck and Media Manager Tankred Stachelhaus say the exhibition embodies the airport’s deep-rooted commitment to embracing local artistry while balancing commercial interests.

Klauck shares how the airport has embraced its regional identity, using art to create connections between travellers and the city’s dynamic art scene. Tankred, with his background as an art critic, brought a keen curatorial eye to the project, ensuring the installations are not just decorative but meaningful, sometimes controversial expressions of the artists’ interpretations of travel and public spaces.

Düsseldorf Airport’s community-centric mindset led to the inception of Art Walk, which goes beyond aesthetics to provoke conversations about the wider role of airports as spaces for more than just transactional platforms. Klauck also notes the airport’s commercial philosophy shifted during the pandemic, focusing on incorporating smaller, regional brands alongside global partners.

Art Walk not only enriches the traveller experience but also reflects the airport’s strategic vision to be a “destination of excellence”. By integrating bold and sometimes controversial artworks into its landscape, Düsseldorf Airport fosters meaningful conversations and connections, positioning itself as not simply a transit hub but a gateway to the soul of the city and the Rhine-Ruhr region.

It also demonstrates how transportation spaces can transcend their conventional roles, offering travellers unexpected moments of inspiration and a deeper connection to the destinations they visit.

Q&A

Martin Moodie: Pia, you’re clearly not afraid of having empty spaces as contract tenures end and commercial operators come and go. In fact, you embrace those spaces and do bold things with them as we see with the Art Walk exhibition and with the introduction of additional local and regional brands. Tell me more about that philosophy.

Pia Klauck: Yes, that’s correct. Especially in recent years [through the pandemic] there was always the attitude of “Oh, life is bad,” and at some point, we said, “No, we’re not taking it anymore.”

Our philosophy – being embedded in this huge catchment area with 18.5 million people living within 100km of the airport – is that the region is so important to us, and we are so important to the region.

At some point, we embraced that and decided, “No, we don’t want to only play with the big players.” Of course, we have Heinemann, Avolta and Lagardère, which are important players because we’re still a commercial airport. But we believe our customers also expect a more regional approach.

Tankred and I had always talked about our connection to the city and being an artsy city. This is the core of the city and we wanted to do something about it and with it.

With that in mind, we saw an opportunity. At Düsseldorf Airport, we have very strong landside space. We have three individual piers that stand by themselves but are connected by a very strong landside.

The landside business in travel retail is always difficult. For the big operators, it’s challenging.

For us, it was always important to have a differentiator, for example smaller regional concepts that we wanted to bring into the airport. This makes way more sense landside for us because it’s usually easier for brands to set up by themselves, especially if they’re a smaller company wanting to enter the airport.

The airport is a big infrastructure with security and all those factors. During the pandemic we did OK and brought everyone through it but smaller brands and local brands were hit left and right by the aftermath. Suddenly, we had something like eight free spaces to fill. We didn’t want to change our approach, in that we wanted to differentiate through smaller brands. But smaller brands were very much more hesitant to come to the airport, because they’re like, “Oh, the risk is so big.”

But airports are always built for eternity – that’s something. So, we had to change our processes to allow smaller brands in without them requiring significant investments. We have our pop-up stores… stores that are basically already fitted out, and brands just move in and put in their products and banners. We tried to make it as easy as possible with our processes… we also had to be quicker.

This was a big shift for us. The mentality changed, because we used to be very strict – very German – about timelines and processes. We had to change that. That was a big boat to turn around.

The artwork was a big challenge. You can’t just push it into a store and be done. There are fire regulations, basic questions like who is turning on the lights, who is turning them off, and so on. There are so many things you don’t consider before doing it.

So we changed. We had to be quicker. We now have teams focusing more on short-term leases, working closely with the promotions teams at the airport, and other teams working on long-term contracts with the big players. We kind of always did this on the side, but now it’s established in our structure.

It’s interesting how you balance the commercial aspect because, as you say, you’ve got a business to run. You’re a sizeable airport, so you need the big operators, but there are softer touches to an airport and art is part of that. It’s part of your character and your representation of the city, region and country. How do you approach that balance?

Pia Klauck: Don’t get me wrong, we are still a commercial airport… so we have to make money. But there needs to be a differentiation between making money and, as Tankred says, “Aiming for attention”.

That’s what makes the balance because you want to create an experience, and sometimes that means dedicating a space that could make money into a point of experience to draw people in. Then have them spend money in the store next door because you’ve drawn their attention.

This is always going to be a tension. This will always be a discussion we have, but we’ve decided to find room within the terminal for this. It doesn’t always need to be about the space. Space is one thing, but we’re also discussing how to incorporate art in the future, even if the space is taken, through installations, for example.

Tankred Stachelhaus: We have a vision. We want to be a destination of excellence, that’s our goal. We want to strengthen the airport’s excellence, be a leader in sustainability, and have closer bonds with employees and the region. That last one is our focus this year.

Düsseldorf is an art city. The artist Joseph Beuys and visual artist Gerhard Richter, who is the most expensive artist in the world, were professors at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. It’s a very vital art scene, and we took that close bond with the city and made it a focus at the airport. The artists want to come here. They see the opportunity to showcase their work here.

I’ve said it before, and I’m not the only one: airports are invariably the first and last place people see in a city. And with that comes a social and civic responsibility.

Art in airports is not a revenue generator at all. It’s about identity. It reinforces what airports are. They’re not just about getting people on and off planes or selling things to them or feeding them. They’re about emotions. Airports are amazing crossroads of humanity, and art is a lovely part of that.

On that note, Pia, tell us about Art Walk. Interestingly, you didn’t go for a safe art exhibition simply showcasing all the lovely things about travel.

Pia Klauck: Yes, that was a big conversation. At some point, we asked ourselves, “Do we want to be a gallery?” We had these ideas in the past, but we thought, “No, that’s just so lame. What does it stand for? What does it mean? How do we want to use the spaces that we have?”

You can always put pretty pictures on a wall, have great lighting and so on, but we decided that if we’re going to be a connector to the region and to the Düsseldorf art scene, it needs to be bigger.

So, we wanted the bigger names and maybe the controversial ones as well, artists with different views on travelling and air traffic. We’re deeply connected to the city, and we know a lot of people who are similarly connected. Tankred knew the right people to talk to. It was a joint effort. I think there was a project team of 15 people trying to realise it.

I’m not a huge art person. I see a picture and think, oh that’s a pretty picture. But from the very beginning, it was very clear this wasn’t about pretty pictures. It was connection, it was about travel. It was about the connection between travel and art. And that is the differentiator. We didn’t want to just make use of space to make it look pretty; we wanted everyone to see that an empty space is being used for something meaningful. We made art out of that empty space. That was very important to us.

When it comes to the artists, we have a highly respected representation of many different artists and styles. Some are more sculptural, but each has its own interpretation, good and bad. There’s so much controversy about airports, so why hide it? Let’s have that conversation. We want to have these conversations. Tankred is the art expert. He taught us a lot about art, and I learned a lot from him.

Let’s be honest, there was controversy. Some of the art makes you think, OK, this isn’t just about flying and freedom. We had discussions about whether this was feasible for an airport, should we do this as an airport, and we decided we would.

Tankred Stachelhaus: In my former life, I was an art critic for the newspaper. So I had some connections in this area, worked for some magazines, and wrote art critiques and interviews.

I had the vision that we wouldn’t just decorate some empty shops. We wanted to make a statement, to respect the art scene, and to create something relevant and strong. We gave the artists all the freedom they needed. One piece, by Gereon Krebber, was a sculpture he had already created, but he chose to show it here, which was a strong decision. To some people, it looked like bombed houses. This piece represents our position as the port of the world. We are a gateway to the world, and within these empty shops this piece makes you think about the world. It wasn’t the artist’s intention; he sees it as a symbol and a ceramic craftwork.

Another artist, Paul Schwer, created a kind of environment for this particular art. He put the installation together. You can see it from the shopping mall to the apron. It’s a strong work.

They’re very strong pieces. Even the title of Paul Schwer’s work, 229 POB, Flying as a Quest for a Place of Longing, ties into what I was saying earlier about airports being emotional spaces. Longing is a big part of that. And the work called Derelict – again that’s a really strong, really bold statement.

Tankred Stachelhaus: We also have Anne Berlit, who worked with prisoners from Essen Prison, just in front of the gate where flights depart for regions where not everybody is free.

Pia Klauck: This exhibition will likely run until the end of October. It was a lot of work to get the artists in and ensure their works aligned with our vision and theirs. So, we’re probably going to take some time and probably do it again next year. Of course, you need to have the right artists who are willing to work together on this. We hope to bring it back again, maybe even expand.

If you don’t have the right space for them to express themselves, it’s challenging. For example, having a view of the runway isn’t something we have in every space, as those spaces are usually very fast turning.

So we’re also thinking about the next step, like going into different installations, maybe light installations, spreading it more across the terminal, and possibly even going airside, which is always a bit more difficult.

We don’t want to repeat the same thing because that’s not art; it needs to be a new interpretation every year. So, we hope to have something again next year.

On the topic of local versus national, I’ve been writing a lot about this lately, mainly regarding food & beverage. In the USA there’s a big move towards genuine local. But it is quite difficult for F&B operators because they make their real money from proprietary brands, where they have better margins. In Asia, according to an interview I did with the head of SSP in the region, it’s a bit different: there’s more focus on local, uber-local or international. What’s the feeling in Düsseldorf?

Pia Klauck: I’m smirking a bit because I feel like we’ve been through this before. You need the big ones, like McDonald’s and Burger King; that’s for sure. And there’s a huge market for it, especially for international customers or even customers with different ethnic backgrounds. If you want chicken, you want chicken.

But being so connected to the region, we’ve always had our small Turkish place because the Turkish community is big in this region. You can’t just have a generic, non-authentic, built-up Turkish Delight situation from SSP, Lagardère or whoever. You need people who actually speak Turkish behind the counter and bring that authentic atmosphere, be the life of the party.

We’ve always had that. We have the German bakery. Germany is a big bread world. So you have to have that at the airport. Of course, there are the bigger brands and the franchise brands, but we made a less commercial decision to also have a small brand.

We also have a traditional Düsseldorf bakery brand called Terbuyken with two locations. This sets us apart from some other airports, but it’s often difficult because it’s a hard decision commercially. Smaller brands are never going to be able to pay like the larger players, let’s be honest.

It’s a balance: we try to implement local brands as much as possible. Sometimes we even bring franchises together. For example, we have a local brand which wants to come into the airport but doesn’t know how, and we put brought them together with SSP to create a new coffee concept, bringing something from downtown into the airport. That sometimes works. It’s easier for us, however, than the SSPs.

Especially in F&B – and we’re in the middle of a tender process now, so there will be news at the end of this year – the local element plays a huge role. Retail is a bit more difficult because of the margins, and it’s not always popular to bring in a small retail brand to a Lagardère and make a franchise out of it.

Usually it’s the people who make the difference. For example, we had a perfume pop-up run by a local entrepreneur, and you could see the difference in sales when she was on-site versus when her employees were there.

During the Euro 2024 [football] tournament, we set up a space for sports fans with jerseys from different regional soccer teams, because it’s so big here, and people watched the games together and debated about the best team. That’s a very German thing – arts and sports. People watched soccer together in the space on a huge TV and took pictures in front of their favourite team. Our CEO even sat with passengers who were just walking in, watching and just having a conversation.

We have something called the Space Walk… a collaboration with a young entrepreneur with a store in Düsseldorf downtown who specialises in really trendy sneakers that are hard to find, like, say the Adidas or Nike with special colours. And, of course, those people are never going to work together with a Lagardère, that’s not how it works. So you need to make it easier for these little stores to come in, be able to just stay there for a couple of months, try it out, almost like a promotion that says, “This is what we do. This is what we can do.” With F&B, we always did it, and we try to emphasise it even more in retail now.

That’s great. Pop-ups give you the flexibility to do that, and if you can remove some of the barriers to entry – and we all know there are many airside barriers – then you’ve got a chance. It gives your travellers a surprise when they come to the airport, doesn’t it?

Pia Klauck: Having a strong landside presence is good and bad at the same time because the big brands might say, “What should we do with this?” because everywhere else in the world it all happens airside. On the other hand, for smaller brands it’s a huge opportunity to just come in and try something new.

Giving our travellers a surprise is exactly what we’re trying to do.

The bigger brands are starting to see how important [bringing in the local touch] is. We are seeing it now in our tender talks. For example, Gebr. Heinemann came back in last year, and they’re developing really well. We work closely with the local team, and now they have the ability to bring in local brands. This was always a discussion we had [in the past] because Heinemann’s system usually required a brand to be displayed across all locations, but that doesn’t always make sense with local products.

Now they have a campaign called ‘We love DUS’, emphasising they are trying to make a difference through those local products. This is something we’re always working very closely on. The approach requires more work because the processes are different. So you really have to have good partners and you have to have a team. However, we’re now more flexible post-COVID.

Sometimes it’s hard and we’re still struggling because there’s the huge infrastructure and the huge airport machine. Even if it takes six weeks to organise something that would take three weeks with a big brand, we are going to take that time. We have the freedom to do that now, and it’s fun to create something new.

Moving back to F&B, I was in Paris a few weeks ago and met Dag Rasmussen, Chairman & Chief Executive Officer of Lagardère Travel Retail. We talked about the three legs of their business. Duty free is mixed worldwide, but F&B – the need to eat – is never going away. Travel essentials – the term says it all, doesn’t it – are also strong. So, it’s interesting that those have become really strong legs for Lagardère.

Duty free is more about what you desire, but the balance is interesting, and there’s so much focus on food. I can’t remember a time when there was more focus on F&B; the Autogrill-Dufry deal underlined that.

Pia Klauck: Absolutely. We have two tenders: the big one for books, press and souvenirs, which includes 12 spaces; and another for F&B, with another 11 or 12 spaces. It is huge for us. It’s going to change the face of the airport a lot when we change that around in 2026. We’ll keep you posted.

Lagardère Travel Retail and Marché [acquired by Lagardère Travel Retail in early 2023] are huge for us. We’ve had a management contract with Marché for over ten years now, and Lagardère was more involved in retail. Now that they’ve taken over Marché, everyone’s wondering how it will change the Marché DNA, which is very hospitality-centric. You can see Lagardère’s influence after taking over, and it’s exciting to see what will happen. ✈️