Introduction: In this guest editorial, The Design Solution takes a journey across the milestone events and trends that have shaped the airport retail experience and will influence its future – from the commercial focus adopted by airports to the design of the passenger experience.

From the late 1940s to the early 1980s

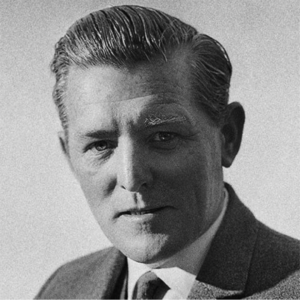

The founding father of the global duty-free industry, Brendan O’Regan launched his retail operations in 1951 from a timber hut positioned outside the terminal at Shannon Airport. Almost 75 years later, the industry’s latest major opening at Abu Dhabi Zayed International Airport is a spectacular 50m-high sculptural building with over 26,000sq m of retail space. Despite the astonishing contrast in these two travel retail locations, each distinctive in its own way, they actually share a core challenge; how can commercial operations be most effectively blended into the passenger’s airport experience?

Across 40 years of airport experience, The Design Solution (TDS) has met that challenge at over 150 terminals across the world, encountering a series of pivotal phases of development in the airport experience that have not only shaped the industry’s past but will continue to influence its path in the decade ahead.

1984-1988

A catalyst to commercialisation

The privatisation of BAA by the market-focused Thatcher government was the ignition point for airports to evolve a radical approach to non-aeronautical revenue. Required by the UK’s privatisation legislation to reduce landing fees by -5% per annum for ten years, the new private operator had a huge revenue gap to fill – and retail was the answer.

Over the subsequent decade, the UK airside experience was transformed by a business model that blended the smartest tactics of the thriving and highly competitive UK off-airport retailers with the opportunities of the airport environment. Driven by a highly experienced team recruited mainly from UK off-airport retailers, out went the formulaic, poorly stocked, generic duty-free shop, newsagent and dull, canteen-style F&B – in came trusted brands to form a hugely expanded offer built on quality, consistency and value, and all presented in a new quality of retail environment.

BAA was the first major airport operator to be privatised, and its scale – and subsequent commercial success – quickly provoked a chain of privatisations across the world, including in Australia, Italy, Mexico, Argentina and India. The privatisation model continues to grow today with over 20% of airports now privatised, though it is significant that the US continues to resist the trend.

1989-1993

Commercial expansion of terminals

The acceleration in airport retailing in the 1990s created a major challenge – where would the space for the shops come from? Airports had always been designed through the lens of aeronautical functions, not for commercial operations and in-terminal experiences for the passenger.

For innovative BAA, the answer lay in a new approach to the planning of its space, including a repositioning of non-key operational functions away from passenger areas and the changing of landside/airside boundaries.

As leisure traffic growth continued, so too did airports’ appetite for commercial revenue – and with it the pressure on terminal space. BAA’s expansion of the Gatwick North Terminal in 1989 was a landmark project focused on commercial development, rather than aeronautical needs. This pioneering project attracted a flood of retailers and brands wanting to fill the new space, setting a strategy that airports worldwide would follow to this day, including Nice Côte d’Azur, Sydney and Budapest airports.

1994-1998

Walkthrough duty-free shops

In its first decade as a privatised operator, BAA pioneered another industry first when in 1995 it introduced the world’s first truly walkthrough duty-free shop in Heathrow’s long-haul terminal (T3).

Deeply involved in the project, TDS Founder and Managing Director Robbie Gill explains how the walkthrough concept initially encountered turbulence: “The walkthrough plan certainly met with a mixed reception. For a number of years there was considerable resistance, especially from the operational side of airport management. Specifically, there were concerns about passengers getting ‘lost’ in the shops, missing planes, and the perceived additional walking distances.

“However, as more duty-free shops across the world adopted similar formats, passengers readily adjusted to the new pathways and the commercial benefits became clear. Walkthroughs deliver 100% shoppers to the retail offer, giving brands a greater exposure.

“We’ve since planned dozens of walkthroughs at airports globally and it’s a concept that can be adapted to almost any airport, though some terminal layouts do require careful planning and re-siting of operational areas to make it fully effective. The blend of increasingly sophisticated targeting of shoppers and more expressive design has made the walkthrough route the backbone of the passenger/shopper experience with a myriad of experiential encounters presented along the passenger route.”

1999-2003

The spread of privatisation

Following BAA’s privatisation, governments began to realise the benefits of bringing private equity into the sector. A major leap forward came when one of Australia’s leading banks, Macquarie, won the bid for Sydney Airport in 2002, going on to major investments in Brussels, Copenhagen, Rome, Birmingham and Bristol.

The success of these privatised operations attracted investors, including the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, and major contractors such as Vinci Airports (active in 64 airports worldwide). This business model has dramatically changed the face of an industry that was almost exclusively in the hands of the state sector.

2004-2008

A growing appetite for F&B

If the typical pre-1990s airport retail experience was weak, the F&B was usually even poorer. At the time, the hungry traveller could at least rely on the French – where landside quality restaurants were the rule, not the exception. From generic cafeteria-style formats, the 1990s saw a shift towards fast-food outlets and then a gradual transformation in F&B experiences as this element became increasingly prominent, both in the traveller’s demands and the commercial opportunities.

F&B inspired a range of strategies. In the US, the trend was for localisation with an emphasis on finding the best local restaurants to enter the airport. In the UK, the emphasis was on the appeal of celebrity chefs, as epitomised by Heathrow T5’s opening in 2008 of Gordon Ramsey’s Plane Food brand, followed by Heston Blumenthal in T2 and Jamie Oliver at Gatwick.

F&B has since become a huge factor in an airport’s ambitions to transmit a distinctive and authentic Sense of Place through the creation of a differentiated experience for the traveller. This also incorporates a major shift in the design of F&B locations; just as the menu needs to be creative and exciting so too must the design of the space.

The post-1990 emphasis on retail revenue often left F&B as the poor cousin, but it has since become the star of the airport show. With continuing reductions in onboard F&B options for many passengers, airport F&B will continue to strengthen both as a driving element in the passenger experience and in its challenge to retail for space in the terminal footprint.

2009-2013

The rise of luxury

BAA’s commercial revolution took the retail experience to a new standard in the 1990s through concentrating on the introduction of off-airport brands, and the industry experienced new momentum with the rise of luxury.

Every region, country and city has different passenger dynamics. European luxury brands have a worldwide appeal, but for some countries they have become a religion. The Japanese arrived first, and when their economy began to stagnate others took over; South Korea, Russia and the most powerful of all, China. It is therefore not surprising that it was in Asia that icon stores were conceived. Louis Vuitton opened a major store in Hong Kong International Airport East Hall and in 2013, both Rolex and Chanel opened their two-level icon stores in West Hall.

For terminals with the right mix of brand-conscious shoppers, icon stores are a necessity. Are they a shop? Are they an advertisement? Simply, they are both. Singapore followed and China has been at the forefront of the trend more recently, with the brands in the domestic terminal at Beijing Daxing a great example. Europe has played its part with Chanel and Louis Vuitton in T5 at Heathrow and now at Paris Charles de Gaulle.

2014-2018

A growing Sense of Place

Sense of Place is an expression that has been in the US airport design industry for many years. Partly fuelled by their mandatory arts programme, but also by regional pride. Elements of local influence began to feature in airport terminal design.

Vancouver Airport is an early fine example, where indigenous arts, materials and character are blended to create a unique airport environment.

As the first half of the decade progressed, a momentum began to build. Major terminals such as Mumbai T2 placed pride in India at the heart of the design inspiration, championed passionately by the team at GVK.

As the years moved on, it has become increasingly prevalent to bring the spirit of the locale into the terminal. The brief from airport owners and operators is that this initiative should be included in terminal designs. This trend now pervades the duty-free industry, with the majority of airports requiring the retail design to reflect their airport, city, region and country. It was not long ago that airport terminals were epitomised by white, grey or silver big span roofs, and shops standard to their operators’ designs, and not the location. This is now history.

2019-2023

Lockdown and recovery

Over the past 40 years, the industry has been impacted by a range of external crises – from viruses and volcanoes to regional conflicts and political instability – but COVID-19 posed an unprecedented threat. Airports planning around steady traffic growth suddenly had no passengers. Projects were stopped, development funds used to stay solvent and desperate negotiations required among commercial partners.

As COVID-19 ended, a more cautious world emerged and the airport industry settled into a period of change. The separation lines between retail and F&B are eroding. Good examples are the acquisitions of Autogrill-Host by Dufry, becoming Avolta; and Marché by Lagardère. This is the start of the merging of a more seamless eating/shopping/drinking experience.

In the industry’s urgency to recoup its losses during the pandemic, the crisis has inspired a major and lasting focus on technology, supporting performance in everything from passenger processing to digital enhancement of the retail experience.

During this time, one the most anticipated terminals opened – Abu Dhabi Zayed International Airport Terminal A welcomed its first passengers and for the first time the world could see one of the wonders of the travel retail industry.

Looking ahead to future trends

- Hybridisation of retail and F&B permeates the commercial offer.

- Airports redefine processes to deliver traveller-centric experiences.

- Environments become intelligent and are able to respond to travellers’ moods.

- Hyper localisation challenges the dominance of global brands.

- Duty free sees virtual shopping outstripping physical sales.

- Digital experiences become personalised to individuals’ profiles. ✈

*This feature first appeared in The Moodie Davitt eZine. Click here for access.