Letter from Shanghai by Kevin Chen |

|

Kevin Chen is a Chinese national living in Shanghai. He previously worked in different parts of China for multinational firms including L’Oréal and Fuji film, and later moved into the publishing field as a Marketing Director, Vice President and Editor-in-Chief for local magazines. He is a columnist and freelance writer and his popular “˜Letter from Shanghai’ column appears regularly on The Moodie Report.com. He can be reached by email on kevinck@vip.sohu.net |

CHINA. I left Shanghai for two months to travel through Xinjiang and Tibet recently and on my return I discovered that the convenience stores near my home had undergone a transformation.

Food products had become much more prominent and the types of imported foods had increased significantly.

I’m not surprised by this change. A few months ago in Hangzhou city centre I saw dozens of chocolate brands imported from the US and Europe. The change there was significantly greater than that at the few convenience stores in my area of Shanghai.

It’s clear – Western food products have arrived, both on Chinese dining tables and in Chinese backpacks.

To attain lift off for a product in China sometimes all you need is one movie. Over the past couple of years two films relating to chocolate have done more good for the confectionery industry than all the commercials of the past decade.

Johnny Depp has emerged as the unlikely Chinese ambassador of chocolate. The US film star has experienced sweet success in two recent chocolate-themed movies Chocolat from 2001 and last year’s box office smash Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Depp has legions of fans among youngsters living in China’s major cities.

Judging by my own personal spend on chocolates – and of those I know – China is still a long way below world average consumption. But no one doubts its potential. Just as I always have an urge to buy perfume in duty free stores, I cannot help but buy chocolates in a supermarket. And people like me are increasing in number all the time.

In 2004 Chinese market research company Sinomonitor surveyed some 70,000 consumers and revealed that the penetration rate of chocolate products had reached nearly 40% in China’s 30 largest cities. This indicated a potential consumer base of some 27 million. By the end of this year the figure will be more like 35 million plus. That is a vast market in anyone’s terms and, excitingly, it has far from reached its full potential.

At present international names are leaping ahead of Chinese brands, which have a long way to go to close the gap. Everywhere you go you find Dove, Cadbury, Le Conté, Nestlé, Hershey’s, Golden Monkey, Ferrero and M&M’s. These brands make up nearly 90% of the entire market. The three largest – Dove, Cadbury and Le Conté – share two thirds of the branded market. Product concentration level is very high, especially for Dove.

“US film star Johnny Depp has experienced sweet success in two recent chocolate-themed movies Chocolat from 2001 and last year’s box office smash Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Depp has legions of fans among youngsters living in China’s major cities.” |

|

The “unlikely Chinese ambassador of chocolate”, Depp in 2005’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Copyright © Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. |

From a consumer brand loyalty perspective, those leading the pack would be Dove, Le Conté, Cadbury, Nestlé and Golden Monkey. And Dove is the leader by some distance.

Last year’s Sinomonitor survey found that China’s chocolate consumers feel strongly about “˜fashion’, “˜quality’, “˜status’ and “˜health’. Some 50.3% of consumers agreed that “I like to go for fashionable and novel items.” About 44.1% picked “I like buying items that have individual characteristics.”

About 59.4% agreed with the statement “I am willing to spend more money on quality items.” 57.6% picked “Branded food products can elevate one’s status.” 71.9% of consumers said: “I prefer products that enhance health and beauty.” 69% ticked the statement “I like to use products which are made of natural ingredients.”

Unlike the Japanese and South Korean markets, which appear to prefer lighter milk chocolates such as those produced by the Meiji brand, most Chinese consumers show similar tastes to Europeans. But according to industry players, sales of original American chocolate flavours have grown rapidly in some major cities. The Chinese appear to prefer flavours with stronger tastes of cocoa. Milk and dark chocolate are both popular.

Pertinently it is the flavour of a chocolate, and not its price, that appears to be the main determinant of sales.

Gifting key to market growth; Ferrero flourishes

A friend working in the industry told me that, at the moment, China’s chocolate market is worth only about US$800 million. That is relatively small. Many companies are still in the early investment stage and have not yet begun to reap big profits. Compared to Europe and the US, chocolates remain only occasional consumer items and not weekly essentials.

This is especially the case in southern China, where many people believe that chocolate is a “˜heaty’ food, causing problems such as coughs or pimples. This is the toughest barrier for educational campaigns to overcome. Because of this belief few Chinese would buy chocolates in the summer. But in the winter months chocolate sales peak. They are especially popular during Christmas, New Year, Lunar New Year and Valentine’s Day.

And therein lies an important point, chocolates are gift products conveying strong emotions and cultural significance. Don’t forget that China is a society that places great importance on relationships. Many Chinese men are keen to please the women in their lives. Chocolates are often used to transmit good wishes to relatives, friends and lovers.

It is this special characteristic of “˜gifting’ that has become the most important form of chocolate consumption. Statistics show that chocolates sold in gift packaging take up some 52.4% of total sales in China. In the chocolate gift market Dove is the number one brand, while Cadbury, M&M’s and Lindt products also rank highly.

I must make special mention of Ferrero Rocher. Ferrero products in general are among the most expensive available in China; but compared to other high-end products they are the choice of many middle-class consumers in major cities. Consumers like the packaging, especially of Rocher, and the flavour. Especially among friends and lovers, Rocher’s heart-shaped packaging is often the definitive choice.

Among more expensive chocolates, price is not the determinant for consumers’ decisions. Instead it is perceived quality that counts and here the packaging and the image of the brand become critical. Hence Ferrero is likely to continue achieving strong growth in China. By using Chinese partners the company has restrained its direct investment in the market but its brand image is good. The company only has about ten direct employees in China; everything else is dealt with by the Chinese distributors.

A word of advice to many European and American confectionery companies: I would say that Ferrero’s is a stable and safe model to adopt. It was dogged by the problem of imitations at first, but over the past two years the government has been clamping down on counterfeits. The brand is well-placed as a result.

Mooncakes and wedding candy

China’s food market has two unusual items which are absent from the Western menu. One is mooncakes; the other is what we call wedding candy.

Either of these far outweighs Western products such as chocolate or cheese in terms of sales. In China, if your product can be used as a gift, then no matter whether it’s cheap or expensive, you will make money. What can be constituted as a gift ranges from a US$50,000 watch to a US$5 box of candy.

“To attain lift off for a product in China sometimes all you need is one movie. Over the past couple of years two films relating to chocolate have done more good for the confectionery industry than all the commercials of the past decade.” |

|

Critically acclaimed Chocolat starring Depp. Copyright © Miramax Films |

Mooncakes and wedding candy are special items from China’s traditional food market. Each year, a month before the mid-autumn festival (on the 15th day of the lunar calendar’s ninth month) a mooncake battle breaks out in China. Confectionery stores jostle to create the most distinctive and most festive mooncake of the season. Price-wise, mooncakes can be out of this world. Not only do prices rise annually, but in every city these days, you can find ever more expensive mooncakes. I remember seeing a tiny mooncake with a price tag of over US$1,000.

The day after the festival, everyone forgets that mooncakes ever existed. Even if stacks are left in the shops, there is only one place for them – internal distribution to employees as freebies.

Mooncake is a distinctive pastry, traditionally filled with lotus seed paste or red bean paste. Wedding candy, on the other hand, is just normal candy. The only difference is in the packaging which is often red or bears auspicious themes such as happiness or blessings. Red is China’s national colour for festive joy and all things lucky.

How big a proportion of the market does it represent? As living standards inch upwards, people pay more attention to weddings, resulting in a burgeoning wedding candy industry.

According to government statistics some 20 million couples get married every year in China. If you go by the estimate that each couple spends some CNY500 (US$6.20) on wedding candy, then the market is worth about CNY10 billion (US$1.2 billion). This would represent about 18% of China’s candy market. In certain districts, such as Wenzhou in Zhejiang province, this could amount to 60% of sales.

A friend predicted that, just as some companies have developed distinctive brands for their mooncakes, so too will the wedding candy industry develop in a similar fashion. In time several key companies will dominate the action – and the rewards.

Mainland Chinese and Taiwanese, Hong Kong, Singaporean and even South Korean companies are dominating these two vast sectors. But judging by the management structures and capabilities of Western companies, they are well placed to drive such categories to another level. They will find novel ways of packaging and work with local staff who understand the Chinese culture to fine tune the offer.

In the overall sweets market, apart from the dominance of Shanghainese brand Dabaitu (literally Big White Rabbit) in milk candy, Western companies already have the advantage. Foreign candy companies – such as Johnson & Johnson, Belgium’s Guylian and Germany’s Ritter – are moving fast in China, and more international firms are set to find success, though profitability will never come easily or quickly.

Western firms haven’t got a grip on mooncakes and wedding candy – yet. Until they do, tens of thousands of Chinese firms will continue competing with each other in a fragmented but enormous market.

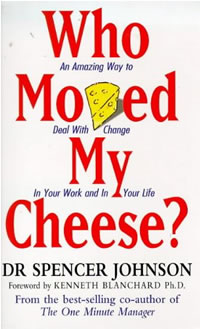

Who moved my cheese?

If you use the Chinese language search engine to look up the Chinese term for “˜cheese’, you will find over a million pages. But most of the hits have nothing to do with the food product we know as cheese. The only reason there is a term for cheese at all is that the American book “˜Who moved my cheese?’ [a book on change written by US author Spencer Johnson, co-writer of ‘The One Minute Manager’ – Ed] was translated into Chinese. It sold over two million copies in China and some 500 million people know the phrase well.

“The only reason there is a term for cheese at all is that the American book “˜Who moved my cheese?’ [a book on change written by US author Spencer Johnson, co-writer of ‘The One Minute Manager’ – Ed] was translated into Chinese. It sold over two million copies in China and some 500 million people know the phrase well.” |

|

Who Moved My Cheese? Dr Spencer Johnson Copyright © Reed Business Information Inc. |

As a result, numerous people use the word “˜cheese’ to describe things that are necessary to a person, a city or an enterprise. Even if they have never actually eaten it, they regard cheese as a good thing.

Until recently cheese was barely sold in China. Even in the major cities, it is a recent arrival on supermarket shelves. Coincidentally, cheese arrived around the same time as the best-selling book. And companies that import cheese are few – mostly those that deal with foreigners, such as five-star hotels and restaurants.

But over the past two years more than a dozen companies have begun mass production in China. The main mode of operation is a joint venture with investors from Australasia. As a result, cheeses are appearing on supermarket shelves with increasing frequency.

As the pace of economic activity has increased, the numbers of Chinese returning from abroad have also increased rapidly. As a result, Western restaurants and food products have developed fast. Cheeses are gaining popularity amongst consumers, and import figures have also grown accordingly. In 2002 China imported about 2,533 tonnes of cheese. By 2003 this had increased to 4,614 tonnes. In 2004 the country was consuming 10,000 tonnes.

Cheeses sold in Shanghai include four or five Chinese brands. These are priced at a lower rate than the imported brands, which come mainly from Holland, France, Australia, New Zealand and Belgium. More exclusive supermarkets can offer over 40 types. But at the moment there isn’t a dominant market force. Kraft, also a giant of the confectionery sector, shapes promisingly as a future leader. But Chinese brands such as Yili, Mengniu and Brightdairy also now believe that cheese will be an important product in the future and are spending serious time and investment developing their offers.

Educating Chinese middle class consumers to eat cheese will take time. But it took only a few decades to get the Chinese consuming milk, despite the fact that for thousands of years they never had a taste for it.

To understand the complexity of the cheese market in China, turn your eyes to Shanghai, currently the largest market. To many Shanghainese eating cheese is a consumer behaviour or memory dating back over 80 years. But in many of the big cities with populations numbering over 6 million in central China, many people have never seen cheese, let alone tasted it.

A potential commercial graveyard

Many multi-national food companies have invested much but reaped little in China. Cadbury lost hundreds of millions in China in 2002. According to industry players, that year was the watershed for China’s confectionery industry. The entire market fell by some -30%, and chocolate sales fell most.

The owners of China’s leading chocolate brand, Dove, also lost money. The reason was that companies were initially too optimistic about 2002 trading opportunities. They used high pressure sales tactics, overstocked, and as a result created market chaos. They were punished swiftly as unsold and perishable goods piled up in distributors’ warehouses.

Since then Cadbury has created new forecasting models, reformulated its sales strategy, successfully introduced gift packs, and increased its budget for promotional activities by +20%. The company is now back on track, chastened but still convinced of the huge potential the market offers.

Swiss rival Nestlé found things even tougher. Last year, sales of its milk powder were hit hard by claims that it contained excessive iodine levels. The company eventually apologised, but it had adopted a low-key attitude when the news first broke, insisting that the milk powder was in line with international standards and refusing to recall the product. As a result the story was reported repeatedly, threatening to turn into a national scandal. This cost Nestlé greatly in terms of image and market share.

I am a loyal consumer of Nestlé coffee and other of the company’s products. But this episode offers many lessons to international brands. In today’s globalised economy, maintaining a brand’s integrity requires huge effort. China is no different – in fact the need may even be greater. Any company wanting a long term share of the Chinese market must treat its consumers just as it would in any other country.

MORE LETTERS FROM SHANGHAI

Letter from Shanghai – A watchful eye on the market – 18/08/05

Letter from Shanghai – why China’s airport retailers need to improve their act – 15/07/05

Letter from Shanghai – Chinese consumers rekindle their fondness for fragrance – 20/02/05

Letter from Shanghai – Can Chinese brands make the grade on the global luxury stage? – 19/12/04